We need a new Admissions Code

The Parliamentary Commission report into Youth Violence is published today (March 26th 2020). It includes a set of recommendations from various fields, including housing, policing, employment and education. There are seven recommendations for education, one of which is that the ‘school Admissions Code should be revised and include the return of all powers for admissions to Local Authorities’. This includes giving local authorities the powers to direct the admission of a student in any school whether primary, secondary, maintained, academy and so on. I have led on the education section and in this blog will lay out the rationale for this recommendation and some of the others. This is a companion piece to my reflections on the Youth Violence report, and expands on some of its points.

It is clearly difficult timing for the report amongst everything else that is going on nationally and globally. When this is over the vast majority of children currently being home educated will have a school to go back to, but many will not and the mechanisms normally in place to enable their return are not in place.

Summary

The reasons why a new Admissions Code is required which includes the return of all powers for admissions to Local Authorities are

1. In essence, the current code does not work and is not serving the interests of children. The numbers leaving education before the age of 16 and not returning are very considerable and growing quickly.

2. Ofsted is very aware of the problem but is not the right vehicle to change it.

3. The schools with the highest rates of transition are able to move on their own children in the safe knowledge they will not be forced to take on new ones.

4. There is a high profile on young people staying in education, employment or training from the ages of 16-24, and schools are held accountable. Yet tens of thousands are out of the system before this age without the commensurate profile or accountability.

5. The costs and risks to the children of not completing their education are considerable, as are the risks to which they are exposed. This also applies to their families and wider society.

6. A public health approach to resolving youth violence, as outlined by the parliamentary commission today, depends on the engagement of young people with public services.

Context

The current version of the Admissions Code can be found here. It was last revised in December 2014 and much has changed since. In November 2013 the Department for Education reported that number of academies stood at approximately 3,500. Since then the number of academies has, as above, more than doubled. Now approximately 75% of secondaries and 25% of primaries are academies, and therefore are their own ‘admission authority’. The number of students in academies is now higher than those who are not.

I emphasise that I am not arguing for or against any particular type of school structure, although it is fair to say that by arguing for this particular change to the Admissions Code it may be taken that way. It would represent a dilution of academies’ independence, and for many that in itself would be viewed as an unacceptable precedent. I am not going to get into that detail, or advocate changes in powers beyond admissions. This DfE flow chart shows how one aspect of the admissions process is different for maintained schools and academies. Both are subject to a ‘direction’ (where a school is ordered to admit a student to its roll) but from different parties and in different ways. In this paper I argue that neither is effective to the detriment of far too many children whom the system is designed to serve.

Elective Home Education

It is somewhat ironic to be publishing this blog in a week when almost the entire cohort of school age children have become home-educated for what looks like an extended period of time. It is worth adding that those with an existing school place have access to a lot more schoolwork and support than the large majority those who do not. The Office of Schools Adjudicator (OSA) publishes details on the numbers year on year. Parents are not required to register as home educated, so any figure is likely to be an underestimate. Also, the numbers are changing all the time as some children will come in and out of home education within the course of an academic year. Note that this is not a judgement on the merits of home educating children, but on the trends in recent years particularly where they point to the ‘decision’ to do so not being made for positive reasons. The figures are startling.

In March 2020 the OSA reported on the 2018-19 academic year and stated that 60,544 were home educated, a rise of almost eight thousand on the previous year. On average over the last four years the figure has increased by 20% per year. According to the Association of the Director of Children’s Services survey 2019 the number of home educated students has more than doubled in four years. Although the ADCS gain their figures from a survey distributed to local authorities the rate of increase is very similar to that of the OSA as an average of 20% per year for four years will double any figure. The OSA’s reported percentage increase for 2018-19 actually brought the average rate down, and it will be interesting to see if this becomes a trend.

The ADCS also reported that ‘at any one point during the 2018/19 academic year, a total of 64,787…were known to be home-educated in 125 responding LAs, meaning it can be estimated that somewhere in the region of 78,781 were known to be home educated in England. This figure is higher than the number of children in care in England….62% are either in key stage 3 or 4’. Very approximately the figures represent 1 to 2 per cent of the school population and, given that the large majority are of secondary age, approximately 2% or one in fifty. This varies considerably between and within local authorities.

It is possible that some of the increase is due to parents or their children finding that today’s curriculum is not to their liking or that technology makes home schooling much easier than was the case. It could also be due to a lack of resources in schools for meeting special educational needs, and there has been no shortage of reporting on that issue. In February 2019 the Children’s Commissioner published a report entitled ‘Skipping School: Invisible Children. How children disappear from England’s schools’. The report states that ‘it is sometimes schools themselves that put pressure on parents to remove children who don’t ‘fit in’. This practice, known as off-rolling, can amount to informal, illegal exclusion…Some schools are believed to have pro forma letters ready for harassed parents to sign, agreeing that their child would be better off home educated, when they come to meet the head after yet another problem. It is unacceptable that some schools are washing their hands of children – particularly the most vulnerable – in this way’.

The report showed that ‘very few schools are responsible for the majority of moves into home education. Roughly nine out of ten schools only saw 0-2 referrals into home education a year, but for a tiny minority of schools it can be more than 15 a year.’ The graph below from the report shows this very clearly, with a very small minority accounting for a high proportion of the figures.

In April 2019, following a consultation the previous year, the DfE published ‘Elective Home Education: Call for Evidence 2018 Government consultation response’. The report stated that ‘the government does not believe that the significant increase in children deemed to be educated at home which has taken place in recent years – some local authorities have reported a doubling of numbers – has arisen from any significant growth in those who believe in the virtues of home education for its own sake. Rather, it believes that the factors leading to a significant proportion of the children now receiving education at home are more negative. They include difficulty in obtaining within the school system what parents see as adequate provision (especially for children with special needs); disagreement with schools about academic or behavioural issues; and a perceived lack of suitable alternative provision for those children who would benefit from it. The report does not go as far as the Children’s Commissioner, but it does acknowledge the issues albeit with some distance between a ‘pro forma letter for harassed parents to sign’ and a ‘disagreement about academic or behavioural issues’. The figures are there either way. As one example in March 2019 the Hackney Gazette reported a 238% increase in a single year within that local authority.

In October 2019 Ofsted published a report entitled ‘Exploring moving to home education in secondary schools’. This estimated that 58,000 children were educated at home, a higher figure than the equivalent from the OSA for the same period. It also added context that ‘a disproportionate number of children who are removed from the school roll of a secondary school and do not move to another setting have special educational needs, are from disadvantaged backgrounds or are known to social care services, or have a combination of these characteristics’. Whether the concept of home schooling has become more popular or not, the ‘disproportionate’ nature of it is a serious cause for concern.

Anne Longfield, the Children’s Commissioner called for a compulsory register of all home educated children in February 2019. I would go further and say that local authorities should have both the resources and responsibility for maintaining it and should also be accountable for quality assurance and the numbers in their area. If they find clear evidence of immoral practices by schools they should have the means to follow up, present their findings to the DfE and Ofsted and expect an appropriate response.

Off rolling

A new Ofsted framework was launched for the 2019-20 academic year and included a much higher profile for off rolling. Paragraph 254 defines the process as ‘the practice of removing a pupil from the school roll without a formal, permanent exclusion or by encouraging a parent to remove their child from the school roll, when the removal is primarily in the interests of the school rather than in the best interests of the pupil’. For anyone who would like an introduction to the mathematics around why off rolling can be very advantageous to the school’s headline examination data should read my blog from last June. For those reading this and feeling incredulous as to how a school would engage in this behaviour and breach education’s version of the Hippocratic Oath, you have my sympathies. I recommend you look at this YouGov survey commissioned by Ofsted for a little more detail.

Another recommendation in the education section of the Youth Violence Commission report is ‘Central Government should commission a review to monitor the impact of the new Ofsted framework on levels of school exclusion and the harmful practice of off-rolling’. The effects of the coronavirus mean that there will likely be no more inspections this academic year so I would advocate this work happening sooner rather than later, obviously under the constraints of the current circumstances.

I acknowledge the case to wait for a full academic year of inspections under the new framework, but counter that by saying after a sustained period away from school the most vulnerable students will be in an even more disadvantageous position so there should be no delay. It is also possible that the high profile of the issue will act as a deterrent to schools, but my view is that it is likely to be insufficient and plenty will carry on if they see it is in their interests.

John Roberts from the Times Education Supplement reported in November 2019 that André Imich (the DfE’s adviser for special educational needs and disability) had ‘welcomed Ofsted’s crackdown on off-rolling’ and that ‘he had not heard of the term “off-rolling” two years ago but said he was pleased that it was now being dealt with’. He also said that ‘there were concerns that some schools were not welcoming to children with SEND but that it was hard to get concrete evidence of this…He also highlighted concerns that some schools are not welcoming to children with SEND.’ This highlights two of the key arguments for a revised Admissions Code. The first is that parents of children with particular needs (I am referring to those who may appear on a school’s SEN register but would not qualify for an Education Health Care Plan) can find it difficult to access what they need. The second is that once a child has left the school system, through whatever means, it can be very difficult to get back in.

Ofsted is in no doubt that off rolling is an issue, but to date very few schools have been found by the inspectorate to be engaging in the practice. John Roberts also reported in January 2020 that six schools have been found to be off rolling by Ofsted of which two were under the previous framework. The report states there are other reports where the issue is mentioned, but Ofsted does not appear to keep or publish figures. Of the four under the new framework, one was judged to be good (technically pupils had been taken off roll, but it was not described as off rolling), two judged as ‘require improvement’ and one ‘inadequate’. This hardly constitutes a ‘crackdown’.

Ofsted published data in the Annual Report 2018-19 showing that over 20,000 students left between years 10 and 11 from January 2017 to January 2018 and for half of them destinations are unknown. The size of the number, along with the fact it is very late in a child’s education may be taken of further evidence that the official home education figures represent a significant underestimate. In the same report Ofsted stated there were 340 schools (up from 300 in the last year) with high levels of movement of this type. In addition, it reported that in the 2018-19 academic year 100 schools with ‘high levels of pupil movement’ were inspected and only 5 found to be off rolling.

Off-rolling is clearly a problem, but it is also extremely difficult to prove. It is not a surprise that they have found so little to date and this is not because of any issue with their motivation. An inspection team has a challenging task at the best of times with the range of evidence they have to collect in a short space of time. This is even more the case with the type of inspection which schools previously judged ‘good’ receive when fewer inspection days are available. A team of inspectors, which is frequently as small as two, do not have the resources to unearth an entrenched issue within the confines of an inspection. Investigating this properly, by which I mean interviews with families of former students and with existing or previous staff, would likely take weeks if not months.

In addition, Ofsted inspections only take place every few years, and for those previously judged to be outstanding it could be more than ten years. For a new school, which includes those who become an academy or are ‘rebrokered’ from one academy group to another, they are safe from inspection for at least the first two years of their existence and much can happen during that time. Inspection is the wrong tool to look into this issue, or at least to be the leading source of enquiry.

Exclusions

The topic of exclusions has had more publicity over time, and in general is better understood by the wider public. The recommendation around exclusions is also one of the key ones in the Youth Violence Commission report, namely that ‘central government should provide significant and immediate increased funding to enable schools to put in place enhanced support necessary to avoid off-rolling and pursue an aspiration of zero exclusions’. Technically this is two recommendations in one. There is nothing to say that if schools were allocated all the resources they have lost in recent years that they would universally pursue an aspiration of zero exclusions. Similarly, it infers that it is much harder for schools to avoid exclusions if it does not have the resources. The cost of a student at an alternative provision placement is around three times that of mainstream, very approximately £15K versus £5K. In the middle is a group of students whose cost to the school is somewhere between those two figures but for whom no additional funds are received. Even if the student does have an Education Health Care Plan, which does insulate them to some extent from a permanent exclusion, the school has to find the first £6K of the cost of their plan from existing resources. This middle group can absorb a lot of capacity, particularly from the kinds of support staff whose numbers have either reduced significantly or are no longer in schools. The inclusion coordinators, learning mentors, behaviour managers lost to the system could work miracles in keeping the most challenging in the classroom and the right side of the line. Without significant additional resources, particularly in the most challenging areas of the country, schools will find it ever harder to achieve laudable aims.

In 2017-18 there were 7,905 permanent exclusions, which was up 2.4% on the previous year. It is a significant rise but also the thin end of the wedge when compared to the numbers of home educated children. The increase of home educated children in the last year alone is the same as the total number of permanent exclusions. The number of fixed term exclusions went up by a greater degree, by 7.6% to 410,753, but at least those children still had a school to go back to and were not lost to the system. Having said that it is also likely that those who suddenly left a school and were not found elsewhere had a disproportionate number of those exclusions. Beyond this if a student with previous fixed term exclusions, or a permanent one, is no longer in a school then they are not in a position to be excluded again so the numbers are lower than they might have been.

Local authorities and admissions

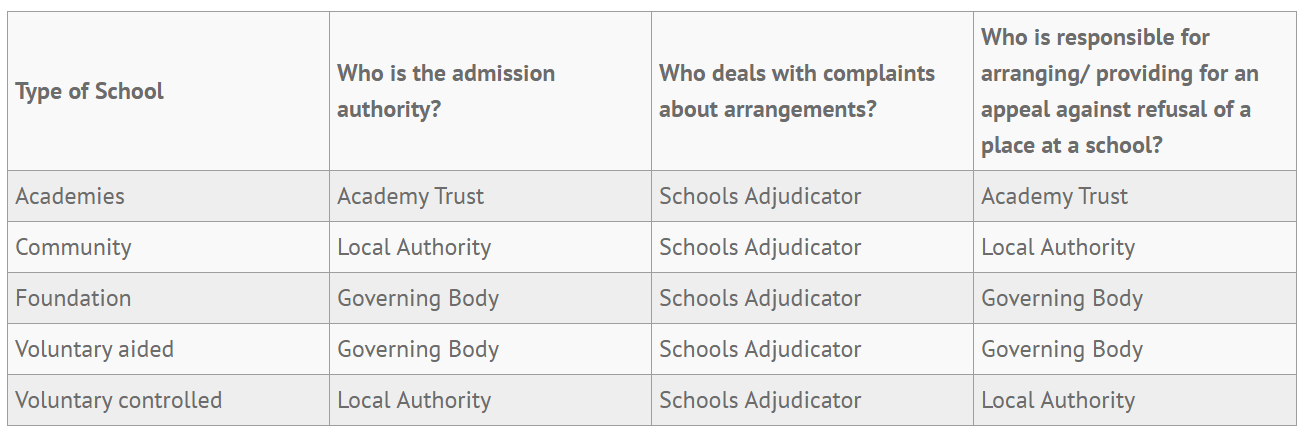

The differences in admission arrangements is laid out in the table from the Admissions Code below.

This is the theory, in practice the differences currently do not matter very much. Part of this is, in my view, about a lack of resources, which is why a further recommendation in the Youth Violence Commission report states that central government should increase resources for local authorities so they can deliver on all of their responsibilities for children, including on school admissions.

For clarity, the same principles and responsibilities apply whether a child is transferring from primary to secondary school at year 7 as they do when a child is out of school for whatever reason and needs a new school place. The most recent annual report from the Office of the Schools Adjudicator states that ‘the overall impression from casework and local authority reports is of an admissions system that as a whole works effectively in the normal admissions rounds and that in those rounds the needs of vulnerable children and those with particular educational or social needs are generally well met. There remain concerns about how well some vulnerable children fare when they need a place at other times’.

It is not just about resources, but also about inclination for local authorities to act. Although this does vary from one local authority to another, overall local authorities have exerted less and less authority over the years. Partly this is a resource issue, as enforcing compliance requires people and money to do so. It is also about relationships with schools, particularly since the coalition government came into power in 2010 and gave thousands of schools the opportunity to academise and move away from local authority control. Giving schools that choice meant they had something over the local authority, in other words ‘we need to be happy with the services you offer and how we are being led or we will go elsewhere’. Ultimately this has led to the needs of a lot of children coming second to the wants of a lot of adults. The explosion in the number of home-educated children means this needs to change.

The evidence persists that it is not changing. In January 2020 the Guardian reported that Chief Inspector ‘Amanda Spielman says some schools in England are putting their own interests ahead of their pupils’ and in particular ‘schools in England that continue to “off-roll” vulnerable pupils…in order to maximise results and improve league table positions’. If the Chief Inspector was surprised at this turn of events she should not have been. Such behaviour has been ingrained in parts of the education system for some time.

The Office of the Schools Adjudicator reports on the number of ‘directions’, when the local authority orders that a student will go on to the roll of one of its schools. Across April 2018 to March 2019 only sixty such directions took place. This is such a tiny figure as to be almost negligible, particularly when at least a thousand times as many are home educated. In effect, the power may as well not exist and extending local authority powers to include all schools will make no difference without the resource or the inclination to use it. Academies can also be directed but the figures reported by the OSA are even smaller. Only twelve cases which originated from local authorities were considered across the whole of 2018-19, and the academy was only forced to admit in two of them. The fact that so few cases were put forward by local authorities should in my view be taken as a strong indication of their faith in the system, as well as their low level of resources to pursue cases.

The report also draws attention to the fact that there is ‘no requirement on local authorities to co-ordinate in year admissions or on admission authorities to take part in any in year co-ordination which local authorities do organise’. In short, once the main processes of admission to primary schools at reception or secondary schools at year 7 are complete a local authority has no oversight, and cannot enforce it should it wish to. The numbers of children admitted mid-year has also dropped from 380,000 to 346,000 in four years, a difference of 34,000. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that this number is almost exactly the same as the increase in home educated students, from 25,000 to 60,000 (depending on whose figures you use). Children’s life chances are falling between these gaps.

A fuller picture emerges when the OSA reports that ‘local authorities are clear that it is only a minority of admission authorities who fail to apply the Code properly or to engage with the local authority when it is seeking to find places for children in year. Local authorities also express considerable frustration at a perceived lack of consequences for schools who behave in this way. Local authorities tell me that they too often feel they have to give up trying to persuade particular schools to admit a child and instead look for places at other schools.’ It should not be the case that local authorities have to rely on the power of persuasion to ensure that children are educated.

In addition, the OSA reports that ‘I was also told by some local authorities that some admission authorities in their area do not to engage fully or at all with the protocol processes. This might manifest as schools failing to respond to enquiries or making the process more protracted by asking for further unnecessary information. They might also refuse to accept a decision by the panel and refuse to admit a child on the panel’s recommendation’. Finally, and perhaps most tellingly, some local authorities said that ‘they did not want to endanger relationships by making or requesting a direction’. In other words, they would rather put their relationship with the school or trust above the needs of a child. This is symbolic of the system as a whole.

Local Authorities have communications to and from schools on a weekly or daily basis. They are far better positioned to know what is going on, and whether a school is acting as it should. They do not have to rely on complaints arriving in order to act, or arrive sooner than a normal inspection cycle would indicate. Their work with the school and the view they have of its integrity and moral fibre are ongoing. In order to properly crack this issue, local authorities need to be able to follow up on their concerns. If they are going to start investigating properly why, for example, many students from a particular school are home educating they need money and time. They also need support of the government and inspectorate to ensure the interests of children come first.

In March 2020 the TES’ John Roberts reported on the DfE’s permanent secretary, Jonathan Slater appearance to parliament’s public accounts committee. He said that he had ‘seen with his own eyes that schools are refusing to admit pupils with special educational needs and disabilities’, that he ‘was concerned that some pupils with SEND, but who do not have education health and care plans (EHCPs), were not being admitted into schools because of poor admission practices’. One of the MPs, Sarah Olney referred to a 2019 report by London Councils which found that ‘significant number of schools were engaging in poor admissions practices to informally exclude SEND children from even starting in school’.

The Timpson Review was finally published in May 2019 and reported in some detail on issues around exclusions, including 30 recommendations which were all accepted by the government at the time. According to the report, admissions are not part of the problem and are barely referenced. The Timpson review does not go far enough, and its remit was not broad enough in the first place. Exclusions are important, but they are a fraction of the main issue which is the number of young people not in school and the difficulties in them getting back in.

I know from my own experience as a secondary school headteacher in two local authorities that it is all too easy for a school to pull up the drawbridge and refuse to admit children. This is with Fair Access Panels in place, designed to ensure children who may require additional resources have a school place. I have attended well over a hundred of these meetings and got used to certain schools never showing up or responding to any communication from the local authority. In the end those schools knew that there was little the local authority could or would do and if they stayed silent long enough the issue would go away. The Education Select Committee published a report in July 2018 called Forgotten children: alternative provision and the scandal of ever increasing exclusions. It concluded that ‘the best Fair Access Protocols work well because they are local and understand the needs of their communities. However, this is not always the case, and it is not right that some schools can opt out of receiving pupils back to mainstream schools or following the Fair Access Protocol’. I have seen these arrangements work quickly and efficiently, but have also seen it hit the buffers. Enforcement is best delivered at the local level and enforcement is nothing without consequences.

Increased budgets, more teachers, better training and so on count for nothing if children are not in school. The long term implications of students leaving school and not getting back in are not known and almost impossible to research. They are out of the system. Their life chances around employment or any engagement in the criminal justice system cannot be tracked. Unlike the costs of youth violence, outlined in today’s report, these costs cannot be calculated, and yet they exist.

Other recommendations

There are three further education recommendations in the Youth Violence parliamentary report. They are

All teachers should receive adequate training in the underlying causes of poor behaviour, including trauma and attachment.

Training for all staff can mean less reliance on a minority, who might often be thought of as a ‘specialist with a particular type of child’ but actually may have no more training than everyone should be receiving. As stated in the report I would advocate this being of all forms of Initial Teacher Training, the Early Career Framework and subsequent professional development. It cannot be dependent upon the teacher remaining in one school for the duration of their career.

Schools should ensure that their specialist safeguarding professionals have the time and capacity to effectively integrate support services, such as social workers, school nurses, centrally accredited mental health counsellors and CAMHS, so that pupils have a single point of reliable adult support.

Without the resources this is easier said than done, but I am not saying it is all impossible in the interim. Most importantly this is about laying down principles for how money is spent if it does return to the system.

All schools’ careers programmes should meet the Gatsby Benchmarks as soon as possible, so that career guidance provision is universally strong and meets the needs of all young people, providing them with access to a diversity of career role models.

The Gatsby Benchmarks have a high profile in every school. High quality careers provision does matter in keeping young people in the system, particularly those who cannot see a relationship between what they are studying and what they may go on to do in the future. The right careers intervention can make all the difference to a disaffected student.

Conclusion

The 1944 Education Act guaranteed ‘secondary education for all’. As things stand we can no longer claim that is in place. The system is not working in the interests of those it is designed to serve and the evidence is both ample and clear from bodies which include the Department for Education and Ofsted. Tens of thousands of children were already at home without a school place when the prime minister closed the schools this week. The public health approach advocated by the parliamentary commission in order to cut serious youth violence depends to a great extent on young people attending a place of education. Without that it is impossible to coordinate services and interventions for those who are most at risk. The Admissions Code must be revised and increased powers for local authorities put at the heart of it.

Bibliography

Admissions Code (December 2014) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-admissions-code–2